I remember a six-month period, at age 11, when I was obsessed with the Victoria’s Secret Angels. I looked at those women’s perfectly tanned bodies — skinny goddesses in their itsy bitsy panties and with cleavage so extreme I wondered how they did not suffocate on their own boobs; yet all I wanted was to become one of them. Barely out of elementary school, I had already been sucked into the game of “if I only I could have.” If only I could have skinnier thighs, more defined cheekbones, even lighter skin, then I would be like the girls in Glamour, Vogue, and America’s Next Top Model. All the teenage-self-love books in the world always assure us young girls that wanting to be part of the fashion industry is a phase of self-hate we’ll eventually evolve out of. For me it went a step further as I was scouted during the 7th grade by a modeling agency. This initiated the daunting prospect that I could actually be a part of this shiny, dreamlike, and completely intimidating industry.

The complexity of my feelings towards being sucked into this world of modeling starts within my family. I have been raised by incredibly liberal parents. My dad, surprisingly, loves that I model and has taken to showing my photos to all our family friends, which makes me uncomfortable. This thanksgiving our dinner ended with a huge argument when he tried to showcase an entire gallery and I protested. My die-hard feminist mother has the opposite perspective. She, though she has never spoken it out loud, is wary of the fashion and modeling world (let’s just call it beauty industry). I understand her opinion. How can you support an industry that is founded upon the idea that you are never good enough? But this did not stop my eagerness to be a part of this corruptly beautiful industry. When spotted by this agency, I could not stop my eagerness to jump and prove that I deserved a chance to become someone.

When my mother and I arrived at the agency a woman came and asked what sports I played, how tall the doctor thought I would be and what my shoe size was. She seemed unimpressed but the woman who originally scouted me kept urging her to take me. They continued to hold a discussion over my head, debating whether I would be of any use to them in this industry, while I sat with as straight as a back as I could manage in order to avoid belly rolls. They ushered me out the door saying that I would be kept in their books. I have only heard from them once in the past three years. I was spotted once after by another significant agency, and this time dismissed even sooner. I would be lying if I said I didn’t feel heartbroken. Eventually a family friend who’s a photographer started doing photoshoots with me, insisting that if I wanted to take modeling seriously I needed to learn my angles. I cannot tell you how many times he told me to suck my stomach in, push my chest out and pucker my lips even more.

Flash forward to the present day and I am more involved in the beauty industry and less certain over whether I should be. I have a constant job with one store for which I do two or more photoshoots a month. This store has become a certain type of home for me, with a very professional air. The people who work there are lovely yet it is always in the back of mind that I would be fired if I were to gain weight or do something with my own body that did not fit the store’s image. Ultimately, no matter how much they like me, I am a tool used to make their store’s products look appealing. Therefore if I myself become commercially unappealing then I have no use to them, it is a practice of objectification but those are the rules of the game.

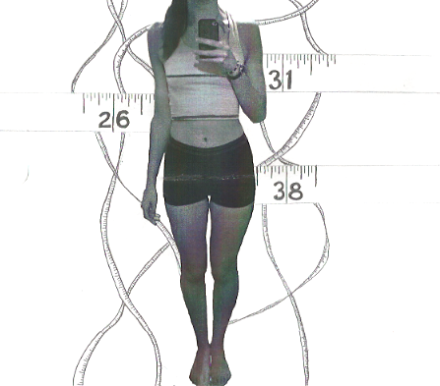

Last photoshoot I was asked to take off my shirt and bra and just wear a hoodie that left my cleavage and stomach exposed. When I hesitated to take off my top the 20 year old male model that I was working with me admonished that “Sweetie if you’re going to model you have to get real comfortable with being naked”. After this remark, off came my shirt, and while I felt am not comfortable since I feel as if the resulting photographs were too exposing and mature I have no legal rights to keep them from being used. These experiences are completely degrading and make me feel incredibly vulnerable but within modeling there exists many moments of fun and oddly enough, empowerment. While many people feel that models are stripped of their voices when in a photoshoot I feel a type of freedom and power. I have the ability to be whatever type of character I choose in photos and it is amazingly fun playing dress-up with all their clothes and make-up. At the same time I’ve become dependent on them for they are the key-hole to the industry I want to be a part of. Whenever I stop by the store they ask if I’ve been signed yet and since I haven’t been they encourage me to. To get signed means to enter the bigger industry of fashion where I’d be constantly going to bookings where some of them I’d get chosen to model and most of them I’d be told “no”. If I chose to make a career out of modeling I’d need to lose 2 inches off my 27in waist in order to fit the requirements. I would also have to be willing to put off college since a full time career as a model and pursuing a degree is nearly unheard of. Reading all of the requirements right now makes me think I’m crazy for wanting to do it but that has not stopped me from setting up a meeting with an agency this spring. I believe I entered a world in which everyone is addicted to. As models, we all know that we are in an industry that takes advantage of us and sometimes simplifies us only to our bodies, yet there is also the community that you are offered and the constant empowerment of knowing that you are what people want see and therefore once you taste a little bit of the industry you desire to submerge your whole self into it.

This writing is not to brag about all of the opportunities I have been blessed or some would say cursed with. This piece is not to rant about how awful the whole industry is. It’s fucking complicated and that is what is noteworthy. I feel beautiful and confident, and modeling has helped me embrace and love my body. I feel comfortable in my 5’11 frame as I stroll down NYC streets. This is in part due to having a job where I am paid because I am thought of as what people want to see. But I am also aware that when I stroll down the street I have become so self-aware that I “put on my face” which means I suck in my cheeks, open my eyes wider and slightly pout. Modeling has not solely made me more confident, It has induced a constant self awareness of my physical appearance. I constantly stare at myself in the mirror practicing my faces, and promising to eat better so I can finally rid myself of my food baby.

I am here to tell you that it is not easier on the other side of the camera. I do not recognize my own body in photos, I despise how I have zoned into the tiniest flaws that cover my body, I cannot recall a time before modeling when I compared myself so constantly to others. Modeling contradicts my moral compass about women, because as a feminist I believe that we all should value ourselves based on internal not external characteristics. One would think that as a feminist I should be able to walk away from this industry knowing that it is for the better and ethically I am standing against an industry renowned for casting aside the hollow bodies of self-destroyed women. Yet I still will continue modeling partially due to being addicted to the empowerment and confidence I am provided with but also because modeling is something I love, enjoy and am grateful for being offered a chance in. I dwell in an intersection between these two identities of modeling and feminism, each of these affect who I am. Ultimately feminism is a mindset that I believe will carry and which will challenge me throughout life. At the same time, while modeling is a phase in my life that will ultimately fade away, it has significantly affected and helped developed my views on beauty and the social pressure to cater to a standard of commercial beauty. Without being allowed access into the beauty industry I never would have developed these perspectives which now affect my view on how beauty should function in our society. I have been allowed access into a space where two worlds of opposite spectrums have collided; this has offered me the opportunity to further challenge and develop my moral beliefs on beauty’s role in the future of feminism, for this I am grateful.

by Emma Morgan-Bennett ’16